A Larger Problem

The Spratleys' eviction is one of many in Virginia during the pandemic. Researchers with The Eviction Lab at Princeton University found there have been nearly 3,500 eviction filings in Richmond alone since March 15.

With many evictions, the details can be murky. The stories can conflict and be hard to follow. But eviction freezes and protections at the state and federal level had one goal: keep people in their homes until the pandemic could be contained. Spratley and his family were left behind.

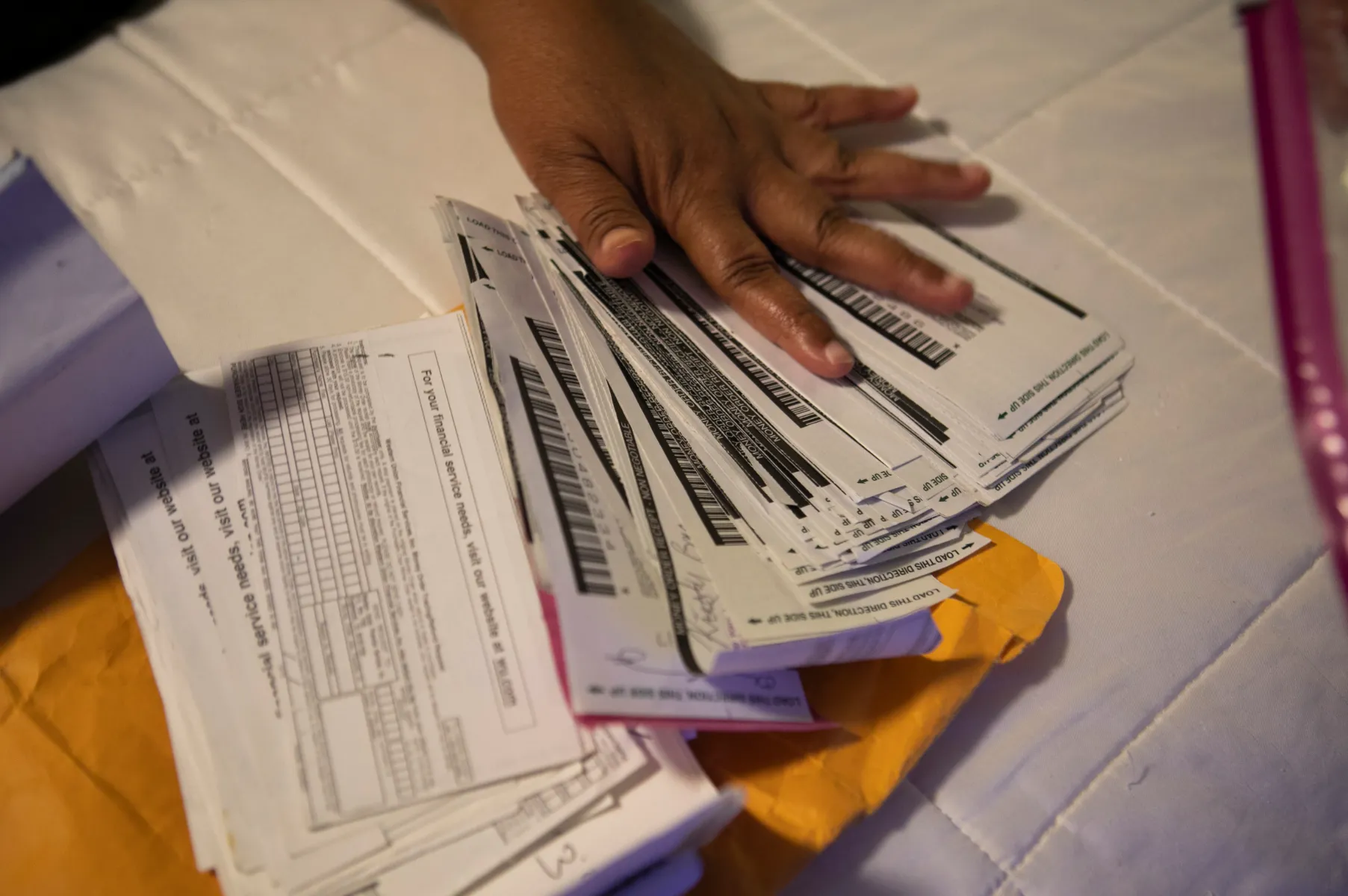

"I got more applications," he said. "But we are still on the waiting list because so many people have been evicted. And they don't have enough to help everybody."

The CARES Act included a 120-day eviction moratorium for renters who receive federal assistance or live in a property with a federally-backed mortgage. It ended July 24, almost a month after Spratley was evicted.

On paper, it looked like his family qualified. The National Low-Income Housing Coalition's website has a searchable database of all the properties that were protected. Spratley's old apartment complex is listed there.

Palmer Heeton, an attorney for the Central Virginia Legal Aid Society, looked into Spratley's case.

"I think in large part, the reason that he hadn't reached out earlier, is because what happened with his case is quite confusing," Heenan said.

Some of the apartment complex was built using federal money — making it eligible for CARES Act protections — and some of it wasn't.

"If he had been living maybe just a few doors or a street over in the same apartment complex, he actually would have been protected from eviction," Heenan said.

Next